Pathway into History

Kiln Industries Fuel an Economy

The Pleasant Valley area was rich…

in both pine trees and limestone. These natural resources were “cooked” in kilns and transformed into valued secondary products.

Charcoal Fuels the Valley

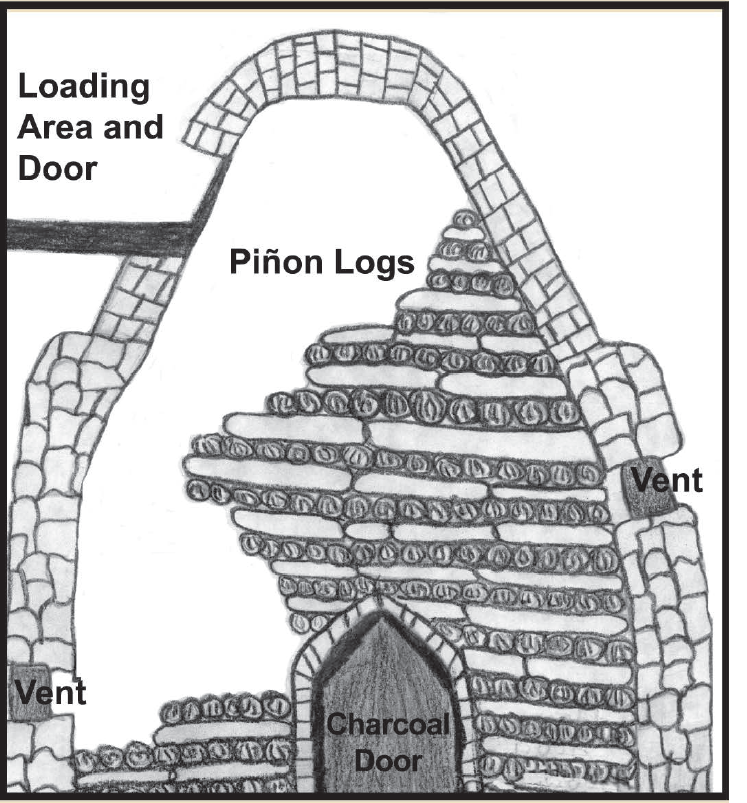

In the north, smelters in Leadville needed fuel to process ore. Without local coal reserves, charcoal was the fuel of choice. Piñon pines, abundant in Pleasant Valley, produced the best grade of charcoal. Trees were cut, stripped of small limbs, then hauled by home drawn wagons to the kilns. Wood cutters and haulers received $1.50 per cord for cutting and hauling the logs. During peak demand in Leadville at the beginning of 1884, charcoal brought the kiln operators about 10 to 15 cents per bushel. Eleven kilns operated by Harp and Taylor produced about 40,000 bushels per month or $4000 to $6000 per month. By the early 1890s, a drop in the silver market and more readily available coke forced charcoal prices down to about 8 cents per bushel. While forges, trains, and heating stoves all used charcoal, the quantity used was minor compared to that used in the smelters refining and processing gold, silver, lead, copper, and zinc.

Limestone Becomes Cement and Plaster

A second type of kiln was used to transform locally mined limestone rock into other products. Crushed raw limestone was placed into an extremely hot kiln. High heat forced the water out of the rock and reduced it to a powdered form. That powder was mixed with sand and water and used as cement. Loose powder was mixed with water and used to plaster walls of buildings and as mortar for bricks.

A Valley of Kilns

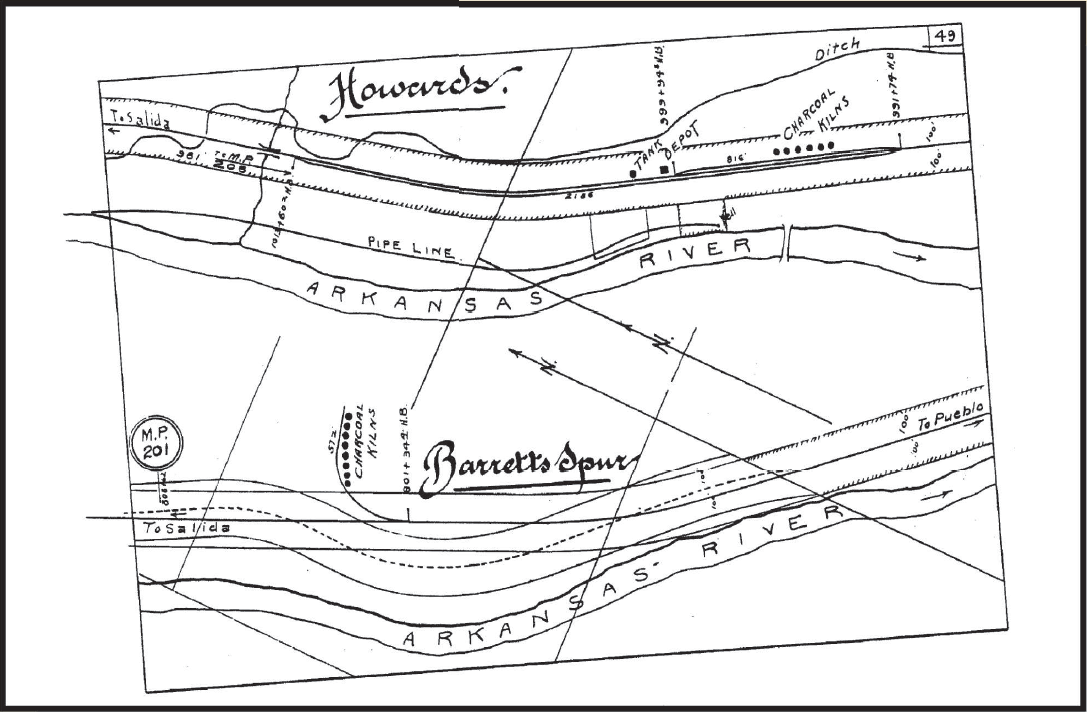

The 1889 Denver and Rio Grande Railroad map shows six charcoal kilns near the Howard siding which were owned by Harp and Taylor and eight at Kiln Gulch along the Barrett spur owned by Barrett. Whenever possible, kilns were located along feeders of the main rail line for easier loading of charcoal from the kiln to the rail cars.

Photo courtesy of the Wayne Leroy family, 1928

Click the image above for a full-sized version

Lime Kiln

A typical rectangular lime kiln remains standing along the railroad tracts in the Arkansas River canyon near Wellsville. Unlike the charcoal kiln the lime kiln fire chamber was separate from the lime chamber. A piñon wood fire in the kiln fire chamber converted the limestone into powdered lime. The powdered lime was shoveled out of the bottom of the kiln and loaded into railroad cars.

Royal Gorge Regional Museum and History Center photo, 2002

Click the image to the right for a full-sized version

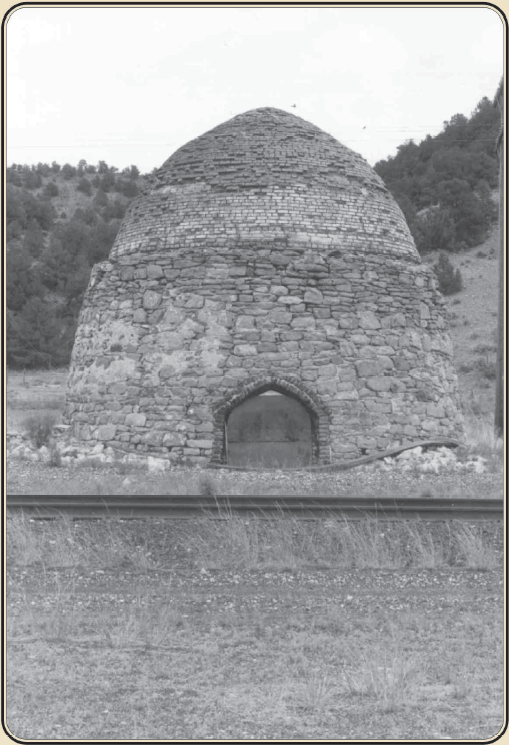

Charcoal Kiln, Howard

Beehive-shaped charcoal kilns in this valley were made of red brick and natural stone measuring about 25-feet at the base and 25-feet high, holding 25 cords of piñon logs when loaded. At peak production, each of these kilns produced about three narrow gauge railroad car loads of charcoal per month. Remains of kilns are visible in Coaldale while bases only can be seen in Howard. In 1988, the railroad demolished all remaining charcoal kilns for public safety.

Photo courtesy of Dick Dixon, 1972

Click the image to the right for a full-sized version

Charcoal Production

Charcoal kilns were arranged in a row for efficient loading and unloading. Green pine logs were layered in a criss-cross fashion. Kindling wood and kerosene started the controlled, slow burn that lasted 3-5 days. The process of loading, burning, cooling, and unloading took about ten days.